This week in the office there was a 5 day training for the Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) part of the study. This has been a bit delayed in being rolled out because there were some procurement issues with the insecticide we are using and staff hiring delays as well. But better late than never! We hired a new Spray Assistant last week and are in the process of trying to hire someone to replace our current Spray Coordinator because he is clearly not up to the job (but that’s a completely different story).

Since we are so short-staffed, we really wanted to have the two drivers attend the training so they could help and fill in when necessary. But if they were out for the week, that meant that no one would be available to drive the teams out to the field to continue the case investigations. After much debate, Kate and I decided that it was a priority to have the drivers attend the training so we made a lot of changes to the normal schedule. One of our field investigators has a driver’s license so we convinced him to drive himself and the study nurse for a week. Then we got a driver from another team to join our camping team for the week, but that meant that the other team needed a driver. I agreed to drive that team three days that week, while Oliver would drive them one day (he’s supervising one of the studies that they are working on anyway), and Davis, the UNAM boss from Windhoek who would be in Katima for the training, would drive them one day.

I knew that this team worked longer hours because I would not see them in the office when I was leaving at 5:30 or 6 pm, but I underestimated how long some of their days were!

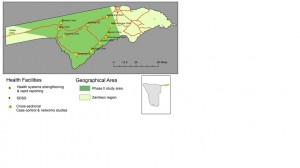

The team I agreed to drive is working on a project called MERFAT. It is a horrible acronym but a pretty interesting project. They are hoping to identify risk factors for getting malaria in the local population by interviewing people who have been diagnosed with malaria and people who come to the clinic, have a malaria test done but are shown to be negative. The study was supposed to finish in March, but with the outbreak that has been occurring they decided to extend it to see if the risk factors have changed between the two settings. They are working with cases from 5 of the 11 health clinics in the area, but a few of the clinics are over 100 km from the office, so this is a very resource intensive project.

The interviews are being conducted at people’s homes (or wherever we find them), so each person is found individually and sometimes they live very far from the health facility. Ultimately it means a lot of time in the car and a lot of driving!

Mondays are always a bit hectic with the staff meeting first thing, then having all of the teams in the small office getting packed and out the door, but this week was even harder because there was all of that plus our admin assistant was on vacation so I had to do her job of giving everyone their airtime and money for fuel, plus making sure that the training was starting and that Davis was getting picked up at the airport. It was a crazy few hours but I finally left with the MERFAT team and we headed off to the clinics. We visited two of the closer ones that day so it took less than an hour to get to the first clinic. However, from there it got tougher.

There are only a few paved roads in the area so once you leave the main pathways everything is dirt. Some of the dirt roads are very good and you can drive 90-100 km/hour on them, but others are like driving along a sandy beach except that you are trying to follow two narrow tire tracks so you don’t accidentally drive over someone’s crops and have them get mad at you. And sometimes the sand is so deep that if you stop for a moment to ask someone for directions, you get stuck and stall the vehicle. Several times. Until you remember to engage the four wheel drive. And even then you might stall again until you reverse a bit and then go forward at speed. These are just a few of the fun experiences I had.

If all goes well, the Research Assistant, Abigail, goes to a clinic and collects a few forms and DBS cards from the cases and controls the clinic nurse saw that week. The form has the patient’s name, age, and phone number so ideally Abigail call them, tells them about the study and makes an appointment to interview them at their home. Abigail is from the area and knows where most of the (unsigned, small) villages are located, so once you contact the person, you can (in the perfect world) drive there and find them at home to interview.

Of course, there are always challenges to what, on paper, sounds easy. For example, sometimes the patient gives the wrong phone number. Or their phone is just off because it has run out of battery and they don’t have electricity to charge it. Or there is no network so you can’t call. Or you drive to the village, talk to someone and find out that the person you are looking for has moved. There are also several villages that go by the same name, so you might have the right village name, but wrong location. Also, people here go by multiple names: everyone has a Christian name, a traditional name, several nicknames, and sometimes several surnames. Not everyone knows all of one person’s name so you might ask someone in the village for “Precious” but she only goes by Precious at work; in the village she’s known as “Mathilda” so the person you talk to says they don’t know Precious, when really they do. Children are the hardest to find because people in the village might not know their name and of course, a lot of children get malaria.

All of this would be easy if there were addresses, but those don’t exist in these rural areas, so you have to do a lot of sleuthing. Which means more time driving. It’s really exhausting work, driving everywhere. On the paved roads you have to really watch for cattle, goats, and dogs in the road, as well as other cars. On the dirt roads, you have to watch out for animals, people walking and cycling, as well as holes, bumps, dips, and other blockages.

Once we found a person and confirmed their identity, Abigail would conduct a 20 minute interview then we would go on to the next person. I tried to be productive in those 20 minutes by reading papers on my laptop, but it wasn’t great. I did get some things done while waiting around, but I would have been much more productive in the office.

Abigail lives just outside of town and it’s difficult to get a taxi from the office back home after 5 pm, and she always works after 5 pm, so I dropped her off at home on the way back, then dropped the study nurse near her house as well. But someone had to go back to the office to put the DBS cards in the freezer and unload the supplies, and guess who that was!

On Monday and Tuesday I got back to the office at 7 pm, then went home and checked my email for the first time that day and had to work for another few hours responding to things and following up with stuff.

I was supposed to get a break on Wednesday when Davis was going to drive Abigail and the nurse, but he scheduled some meetings at the Ministry of Health for that day so I was at it again.

I had a day in the office on Thursday which was a nice break from the field and was amazingly productive. I even got home when it was still light out which was a nice treat.

On Friday, I was back in the field on the far side of the region in which we work. Our first stop was Sesheke Clinic. While Abigail was going through her paperwork, a man came in carrying a young boy on his back. The child, his son, was so ill that he could not even stand up. An RDT test confirmed that he had malaria and it was a very severe case. This boy immediately became a top priority for the nurse on duty because he looked like it was going to die.

Sesheke has a catchment population of around 3,500 people. Typically there are two nurses at the clinic. This week one of the nurses was at a week long training in town so there was only one nurse. The two other next closest clinics only have one nurse each and both of them were also at the training so people were coming from even further afield to get treated here. Imagine living somewhere with 8,000 people and one nurse. There are no doctors for over 100 km and don’t own a vehicle and you can’t afford transport that far. It should be unbelievable, but this is what life is like for much of the world.

The deathly ill child was so sick that he was having convulsions. The first line treatment for severe malaria like this is to give IV artusunate, but the child was thrashing around so much that the nurse could not get the IV in his arm. Since our team has a nurse with us to test anyone who is sick at a household where we are doing an interview, the clinic nurse requested the help of our study nurse in placing the IV. The two nurses worked together while to men held the child down and finally managed to get the IV in and start treatment. The boy’s breath was quick and shallow and his eyes glassy.

In the meantime, a van came in and several people helped a young woman out and into the triage area. She was so sick that she could hardly stand either. She was quickly diagnosed with malaria as well.

The young boy absolutely needed to go to the hospital and the young woman probably did as well. The closest hospital is in Katima, 110 km away. They have 4 ambulances for the entire region. When the clinic nurse tried to call the ambulance driver, he didn’t answer his phone.

Abigail and I quickly decided that we couldn’t leave until we were positive that the boy would get to the hospital. The nurse tried calling several people at the hospital to see about the ambulance then ran out of airtime, so we let her use our phone. She finally reached someone who was able to track down the ambulance driver in person and send him to us. Even when we were told the ambulance was coming, we decided to wait because sometimes they stop to pick up other patients along the way and might not arrive for 4 or 5 hours. This child wouldn’t survive that long and I was ready to put a mattress in the back of our truck and drive him to the hospital myself if need be.

Fortunately, the ambulance arrived in about an hour, which is pretty fast considering the distance traveled, and the boy was taken to the hospital with his father. By that time the young woman had also been treated and was doing a bit better so it was decided that she didn’t need to go but would be observed at the clinic for a while.

Once the emergency was over, the clinic nurse was so grateful for our help. She thanked each of us heartily and called us all angels because we came in her hour of need. She couldn’t have gotten the IV in by herself and even thanked me for bringing the nurse to her. I just wished I had been able to do more. Rarely have I felt so helpless.

It was an intense three hours but I think it has a good ending for those patients, at least. During that time three other malaria cases were also diagnosed but they were not as serious and were sent home with treatment. This outbreak is still out of control and seeing it first hand like that hit home in ways it had not before. Even in town where we get reports of the number of cases it doesn’t seem as dire or as urgent somehow. But when you are at the clinic, potentially watching a kid die, or interviewing the mother of a case who has gotten malaria for the second time in two weeks, it completely changes your perspective on the situation.

This week we’ve also gotten word that several of the clinics are running out of ACTs, the primary treatment for uncomplicated malaria. The clinics get their stocks from the Central Medical Supply at the hospital and when Kate and I went there last week, they only had a few boxes of treatment left and didn’t have enough to resupply the clinics who were almost stocked out. We gave what stock we could to two clinics, but our supplies are not very great. If more medicine does not arrive soon, the situation will quickly go from bad to worse.

There have already been a few deaths from malaria in recent weeks, which should absolutely not happen since it’s so easy to treat this disease, but because money and access is such a big factor, people often wait to seek treatment until they are very ill and have been so for weeks. Sadly, then it could be too late.

Luckily, the young boy that we helped got to the hospital that day and will hopefully recover but who knows what long-term consequences he might have because of this.

Situations like these always put things into perspective for me and make me grateful for all of the advantages that I have based purely on where I was born. But it also makes me angry that anyone in this world today has to live like this. Every life should be valued the same and should have equal access to the necessities of life. I like to think that the work I do helps to bring some more equality to the world, even if it is on a very small scale; that’s why I entered the public health field. Although research doesn’t often equate to immediate effects, I think today I made a difference.